Like jelly in a mould: the flexible brain of marsupial mammals

Being stretchy and squeezable may be the key to fitting the brain in the skull of mammals, including humans.

An international study led by Australian Flinders University’s Vera Weisbecker, with collaborators at the University of Salford, UK, and other institutions in Australia, the UK, France, and the USA, has revealed that marsupial mammals like possums, kangaroos, and wombats appear to have a lot of flexibility when it comes to accommodating their brains into their skulls.

Dr. Weisbecker, who led the study, said: “The brain is one of the heaviest parts of the head, particularly in smaller mammals. But it needs to be placed in a way that doesn’t interfere with the many vital functions of the head, such as seeing, hearing, smelling and of course feeding.

“’Stowing’ a large brain into the head is a general challenge for mammals, which have much larger brains relative to their body size compared to their reptile-like ancestors. It is also a particularly intriguing issue in humans and their primate relatives, which tend to have extremely large brain sizes compared to other mammals.”

“We wanted to use a diverse group of mammals to assess if there is general pattern of brain shape variation in order to explain the ability of mammals to fit their brains into the great diversity of head shapes without interfering with head function. Marsupial mammals fit the bill perfectly because they are a well-understood group of mammals with diverse head sizes and functions.”

The team used CT scanning and 3D visualisation to extract the shape of the brain cavity in the diverse group of Australian marsupial mammals.

Dr Robin Beck, Lecturer in Biology at The University of Salford, who co-authored the study said: “This study shows that there don’t seem to be many restrictions on what precise shape the brains of mammals can take – they are simply the best shape needed to fit efficiently in the skull, like jelly in a mould.”

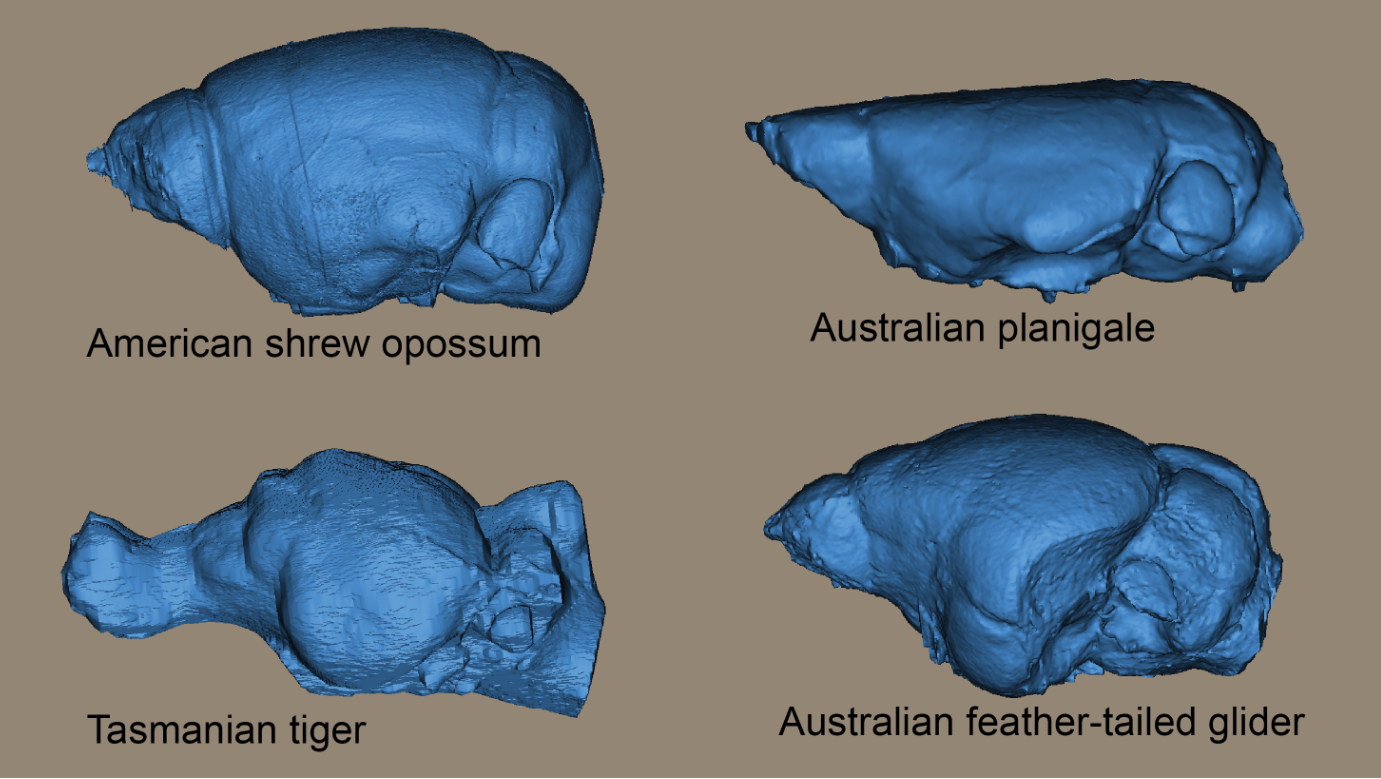

Co-author Dr. Emma Sherratt from The University of Adelaide analysed the data, and the team were in for a surprise. She said: “The biggest difference between the brains is basically whether they are more cylindrical or more globular. We were struck by how extreme this stretch-compress pattern was – we saw brains that look like marbles, and others that nearly look like tubes!”

Another interesting find was the many unusual brain shapes the team saw.

“Within the general pattern of spherical versus stretched-out, we saw some outlandish endocast shapes. For example, some species had totally flat brains, while others seemed to have parts of the brain ‘squished aside’” by the bone around the middle ear.”

The teams find matches well with evidence that the brain of some mammals can change size and shape during an animals’ lifetime.

“We suspect that a flexible brain is the key to success in other animals as well. For example, some crocodiles and ancient coelacanth fishes have extremely long brains, and birds have their eyes imprinted on their brain shape. It appears that the brain is capable of functioning regardless of where it goes in the skull.”

The research shows brain function might not be easy to determine from brain shape.

“We found no correspondence of brain shape with movement patterns, for example, if animals in a species climbs trees, glides, hops, or walks on all fours. We suspect that the overall shape of the mammalian brain is strongly determined by the requirements of the skull. Understanding specific adaptations of the brain probably require investigation of finer detail than overall brain shape.”

Read the full published paper in international journal Evolution.

Image: Some not-to-scale endocast images highlighting the shape diversity of various mammal’s brains.

For all press office enquiries please email communications@salford.ac.uk.

Share: